|

I have half a pilot's license. My checkride was yesterday at Castle. I did great on the

oral exam but decided to postpone the flying portion because the winds

got too strong (17-25kts). Same thing forecast today, so now I'm in

limbo hoping to finish the exam next week. Grr!

Planes drift with the wind. You can't really feel a steady wind, all you

sense is your speed over the ground changes. My plane goes about 120kts

and winds are typically 10-30kts, so my real speed is ±25% which

makes a big difference for fuel planning. A crosswind also pushes you

off course, so you have to

calculate wind corrections. Easy

when travelling straight, but one of the checkride tests is flying

a perfect circle around a

landmark. Not easy with a 20kt wind blowing you off course.

Steady winds straight down the runway present no problem, if anything they make it easier to takeoff and land. Winds blowing across the runway are a different matter; difficult crosswind landings are something every pilot respects. Coming home yesterday I landed in a 10-14kt crosswind at San Carlos, but it took me 3 tries. The biggest problem with strong winds is they're seldom steady. If a wind is 10kt gusting 20kt, your airspeed may suddenly drop 10kts in a lull. That can be a problem if you're flying slow near stalling speed. And gusty winds require active flying to stay pointed the right way. San Carlos has a bunch of mechanical turbulence from the wind swirling around the buildings near the runway. Crosswinds there don't just mean a static correction, you have to sit up and dance fast on the controls like you're playing a videogame. It's kind of fun but very demanding.

Pilots in the US have a lot of freedom. I can fly pretty much anywhere

and land at pretty much any public airport without asking permission or

even telling anyone. If air traffic control is involved it's generally

to help me avoid other airplanes, not to tell me where I can't go. There

are some general rules for safety (at least 1000 feet over cities, for

instance), and some restricted

areas and special rules over places like Washington DC. But pilots

are basically free to go where we want.

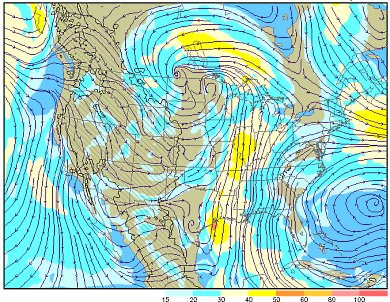

But there are Temporary Flight

Restrictions. Most of these are one day restrictions for specific

events. The blue dot in the Gulf of Mexico is because of the

oil spill: only Coast Guard below 4000 feet. The red dots around

Iowa are for Obama's visit:

can't get within 30nm of his stops. The little dot in

Dallas is for George W. Bush, just 1nm under 1500 feet where it's

probably not a good idea to be flying anyway. Most of the TFRs are

safety or security related and seem reasonable, although it's rough

on business when Obama is vacationing in Hawaii.

Then there's the weird ones. There's been a "temporary" flight restriction over Disneyland since 2003. Why? The 3nm buffer doesn't provide meaningful security; the cynical theory is it stops banner towing. There's also a blanket TFR for sporting events: no flying over large stadiums during baseball, football, Nascar, etc. I don't want to be the jackass buzzing the big game. But it's pretty difficult to know where every stadium is (not all charted) and know the schedule of all major sporting events in the area. Pilots have a pretty good deal in the US, I'm prefectly happy to have some limits for everyone's safety, security, and comfort. I just hope we don't keep expanding the restrictions to make a complex mess that pilots can't understand.

From FAA Advisory Circular 00-6A, "Aviation Weather For Pilots and Flight Operations Personnel". All that's missing from this groovy illustration is the cocktail glass in the pilot's left hand.

It's time to stop using passwords to authenticate users. They were never

a very good form of security and they're only getting worse. The latest

fiasco is Apache

had a breakin with their bug tracker where passwords were logged for

three days. The hashed password database was stolen too, facilitating

dictionary attacks. At least Apache was hashing passwords: there are

plenty of dumbass

sites

that store passwords in plain text.

Password database theft is particularly bad if users use the same password on multiple sites. Yeah, I'm sure you've never done that. I have 560 passwords stored in Google Chrome right now. To any hackers reading: of course all my passwords are different. They're all at least 16 characters, multicase, and use Urdu punctuation. So if not passwords, then what? Four alternatives:

One of the silliest, most preventable reasons for a small airplane to crash is

running out of gas. It happens with some frequency. Why?

Plane design doesn't help. Old airplanes typically have a float fuel gauge whose only standard of accuracy is "reads correct when empty". It's not uncommon for the gauge to read 5-10 gallons wrong. So before every flight I climb up to the wing and put a calibrated dipstick in the tank. And many airplanes require the pilot remembers to manually switch tanks or activate pumps in flight. Some 30% of fuel management accidents have the plane running out of gas while there's still gas in the tank. The primary way GA pilots manage fuel on board is to do arithmetic. You look at the length of your trip, the winds, read some performance charts, then bust out your calculator to figure out how long it will take you to get to your destination at what fuel burn. I might get anywhere from 10 to 18 miles per gallon on a flight. And if the headwind is stronger than I expected or I'm routed the long way, it might take more than that. The 30 minute required reserve is really not enough.

Fortunately the fuel accident trend has been improving. There were twice as many fuel management accidents ten years ago. Part of the improvement is education, part is technology. Aviation GPSes do a good job of estimating and displaying your range with available fuel. And fuel totalizers can very accurately measure how much fuel you've consumed. Still you have to know how much gas you had in the first place, a remarkably difficult thing to determine.

Our cat Ejnar died March 30th. He'd had kitty cancer, then surgery last fall. He seemed to have fully recovered but we knew there was a good chance it'd come back. And so it did.

He was a good cat. He'd clearly been someone's pet, affectionate, social, good with the litter box. He even knew not to jump on tables, although if we left our plates with chicken bones on the dining table they'd be gnawed clean on the floor in the morning. Polite cat, but perfectly happy to help himself when unseen. His favourite things were rabbit fur mouse toys, fish and shrimp feast, the warm air from the heater vent in the morning, and sitting snuggled between Ken and I on the sofa. He was a chatty cat, I still hear his inquisitive "mrowr?" in my mind when I come downstairs in the morning. We miss him.

One of the reporting points we use when flying around the Peninsula is SLAC,

officially

VPSLA,

the Stanford Linear Accelerator. It's a 2 mile long

straight line on the ground, very easy to see, and it's at a convenient distance from the San Carlos and Palo Alto airports for calling in to land.

I'm sure there's some rational explanation for why a high energy physics installation 2000 feet below me would cause my VHF radio to pick up random signals. But aviation is a faith-based enterprise, not science, so when I hear the creepy noise I just whisper "4 8 15 16 23 42" to myself to keep the plane from falling out of the sky. |

||